The Don Moves On: Eddie Day Retires After Five Decades

as told to Thomas Greco

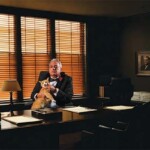

For five decades, Eddie Day has been a prominent and highly respected figure in the automotive repair industry. During that time, he built one of the most successful collision repair shops (Collision Restoration; Fairfield) in the state as well as serving as President of AASP/NJ, and he was a key figure in the merging of the state’s four automotive repair associations. Affectionately known as “The Godfather” to his friends and peers, earlier this summer, Eddie surprised just about everyone when he sold his shop and retired. New Jersey Automotive sat down with “The Godfather” and discussed his 50 years in the industry. So sit back and enjoy Eddie’s journey. Leave the cannoli.

New Jersey Automotive: How’s retired life treating you?

New Jersey Automotive: How’s retired life treating you?

Eddie Day: You know, everyone tells me that I sound and look relaxed. Do I miss the business? No. I thought I would miss it more. I definitely have to keep busy with something because I get anxious. But do I miss being responsible for 25 people? Do I miss 13 insurance companies with 13 different rules? No, I don’t. Not a bit. I mean, it hasn’t been that long, but so far, it’s been great.

NJA: Is it what you thought it would be?

ED: No, I thought I was really going to be messed up, that I would be anxious and grieving and all that shit. But honestly, my office took it much harder than I did because we were closer than most families. It was a tough breakup for the employees. But I needed peace of mind. It was time.

NJA: All right, let’s go back. When did you first realize you loved cars?

ED: My family thought I was a special needs kid because of my illnesses. So my mother was smart enough to know that school was not going to be the answer; I wasn’t going to make it. I didn’t have the confidence, even though she did her best. Toys back then were very rudimentary, very simple. I took every toy apart to see what was going on inside. And then I got to the point where I could actually put the stuff back together, and it worked. So my mom bought an old car, put it out in the driveway and went to a little auto parts store and bought these little SK tool kits. That’s how I got started.

NJA: So you graduated high school, and what happened? Did you go right into the industry?

ED: I was in the industry before that. I was 14 years old working at Koch and Testa Auto Body in Montclair. I got the job through what Bloomfield High School used to call cooperative industrial education. You know, the slow kids. (Laughs) You have to understand, downstairs in the mechanical shop, it was like its own subculture. The kids from the Key Club didn’t even walk through the f#$king hallway. The mathematics class certainly wasn’t there. Okay? They were hard line dopes like me who couldn’t add two and two, but we could put a whole car together.

NJA: What was that like?

ED: Every shop teacher was Italian. They were World War II veterans, and they didn’t take any shit from anybody. They put you against the wall. They would literally pick you up off the ground. I’m not kidding. Frankie Stell – we called him Frankie Bear – Frankie Bear would go to the toughest guy on the first day of class, grab him by the shirt and pick him off the ground to let everybody else know, “Don’t f#$k with me during the year.”

NJA: Wait, that was a teacher?

ED: That was a shop teacher. Frankie Stell. A great guy. His voice quivered when he got pissed off at you. He’d say, “Eddie, I think you’re a nice kid, but I’ll knock your f#$king head off if you talk in my class.”

NJA: Tell me about that first day walking into Koch and Testa Auto Body.

ED: An old German perfectionist metal man. He wouldn’t let you do anything. I remember there was a ’66 Pontiac Bonneville there. This was 1973 or 1974. So that was kind of a new car then. It was dark maroon metallic, a real fine metallic. I remember him sanding it. He painted the right side rear quarter. He polished it. And that’s when I knew I wanted to do this. I just knew. He ran liquid ebony over it, which was a product we used 30-40 years ago, with a tie-on wool bonnet. And then he used cornstarch for a finish. He dusted cornstarch on it and buffed it out. It was like glass. I remember thinking, “Holy shit, what a cool way of doing business.”

NJA: How long were you there?

ED: I was there every summer for three years. And I worked my ass off. He never raised my hourly rate. The minimum wage was $1.75 an hour. So I worked four hours a day, five days a week, and I took home $30. He made me sand with this Coleman gas, and your hands would split open. But you didn’t complain. Then he found out I had an illness. I was taking medication for it. He fired me a half hour later.

NJA: Why?

ED: He thought I was going to have a seizure. He took me into the compressor room, that old piston compressor, you know. And he fired me. So, I put whatever tools I had on my bike and rode home. I got home, and my mother ran over. She asks, “What are you doing home? You’re supposed to be working.” I said, “I don’t know. I got fired.” “What’d you do?” I said, “I took my medication in front of Joe for the first time, and he fired me because I told him I was epileptic.” She said, “You made two mistakes. Number one, you told that man you had an illness. I never liked him. He was a cold German, and I never liked him, and you trusted a stranger with your personal information. Number two, I’ve driven you to work in the snow, and I remember passing body shops – you should have stopped in one of those f#$king shops for a job.” She was right.

NJA: So did you?

ED: I went back and worked at Caldwell Auto Body. The owner was a happy-go-lucky guy. He drank during the day, but he was a nice guy. The place was two by two. It had undercoating all over the floor because he used to undercoat for Claremont Cadillac. The place was a mess. But he made his living.

NJA: When did you decide to open up your own shop?

ED: Well, I worked for HR Auto Body, and then I worked in little garages all over the place. At the time, you could rent a garage, and nobody really bothered you. There was no room in the garage. They were usually so small that when you had a big car, the garage door would land on the bumper. If you painted a car, you’d paint the right side, wait a day later, turn around, paint the left side. There was no room to paint the whole car. Then I started working at Derio Oldsmobile in West Caldwell for a guy named Tony. I was in Florida on vacation when President Reagan fired the air traffic controllers. I was stuck there for a week. When I got back, Tony fired me. I put my tools in the trunk of the car, and I drove away. It’s amazing, the toolbox fit in the back of my car, right? I put the top down, and I drove home.

An hour later, my friend Paul Kaufman called me. He wanted his car painted. He found a garage in Bloomfield. It was a shack. It had no running water, no heat, no bathroom. I would go to the McDonald’s on Broad Street if I had to go to the bathroom. It had a little, tiny air compressor. It had an extension cord. I had used fluorescent lights hanging up all over the place. I had carpet on the doors to keep the place warm. I had two kerosene heaters. And that’s where I started my own business. From there, I worked, worked, worked. Then I met a guy, and I shared a garage in Fairfield with him. I went there with $200 and a toolbox. I had no money. I used his checkbook. I never took a dime from him. I’d put my name next to every check, and I’d pay him back at the end of the week. I remember Matty from Muller Brothers sold me my first 55-gallon drum of thinners. It had my name on it. I felt like I had made the big time. I got credit. I got f@#king credit, you know? Matty started me off in the business. Great man.

NJA: What year was this?

ED: It was May of ’86. That was Ed’s Auto Body/Collision Restoration in Fairfield.

NJA: Was the shop an immediate success?

ED: No. I did wholesale work. I did work for some guys, some shyster that did auction work, but I used to work until 12, one o’clock in the morning. My first wife brought me Thanksgiving dinner and Christmas dinner there. I’d work outside with a drop light. The guy that rented the building to me drove by with his wife at one in the morning, and I was working with a drop light on this old black Bonneville. She turned to him and said, “You finally found another goddamn animal.” That was me.

NJA: But wasn’t the ’80s supposed to be the golden age of auto body?

ED: Oh, no, no, no. We did well. It was too early. I made money. I worked my ass off. It was me and a helper in a two-bay shop. It was the tiniest little shop. I rented the back of the mechanical shop. Then the town shut me down. They wanted a spray booth. I put the spray booth up, but I never got a permit. Then they shut me down again.

NJA: You often talk about the end of the ‘80s being the gold rush.

ED: Well, I think there were a lot of shops that were still doing business the old-fashioned way. There was a lot of money going around. People weren’t afraid to spend money on their cars. They restored stuff. I was probably working cheap because I was a kid. But I worked hard and made money, yeah, of course.

NJA: And then later in the ’80s you became involved with AASP/NJ. How did that come about?

ED: Around 1989 I think, Champion Bumpers’ Steve Bollander brought me into the association. But I really wasn’t ready.

NJA: What made you become interested in it?

ED: I wasn’t smart enough. I needed to know more. I think the shops that join and take part in the association are the smartest people in the industry. That’s why I joined. I wanted to know more.

NJA: You join the association, you’re learning, getting training and sharing ideas, and within four or five years, you’re the president.

ED: I wasn’t ready for that, either! (Laughs)

NJA: What are your memories from that time?

ED: I have trouble with public speaking. I struggle with it. But then again, I was good in a small setting. But as president, it brought a lot of attention I never expected. Because of that title, I met my direct repair partners, and my business took off.

NJA: When you became president, everyone in the association wasn’t exactly on the same page like they are now. How did you get through those muddy waters?

ED: It was tough because you had shops that had a different view on being insurance related. They were telling me that I was going to go out of business. And I remember in the back of my head, saying to myself, “They don’t know it, but they’re going out of business.” Because the guy with the checkbook is the guy you have to connect with. Whether you want to be a rebel or not, being completely isolated from the insurance industry is a death sentence. Look, at least 60 percent of our members have always been direct in one way or another. Or they’re doing fleet or dealership work. They’re being fed by somebody. Maybe I got it a little bit earlier. But I knew that those insurance relationships were important. Especially in the location I was in. My shop was tough to find. Today, if you want to find me, you put in your phone, and a red line drags you right to the shop. People will find you. It’s easy. But back then, it was contentious. Obviously, the Board stuck together, whether one was DRP or not. We represented everyone without judgment. We always said each shop had to make their own business decisions. We stood behind that then, and the association still does today.

NJA: Then a couple years later, you were past president, but you were very much involved in the merger of the four state associations.

ED: I started going to some of the other associations’ dinners and meetings. I became very close with Nick Kostakis, Lee Vetland, Joe Lubrano and several other guys from Central and South Jersey. They were great people. They were smart, decent human beings. I knew they wanted the best for the industry. We knew we couldn’t accomplish what we needed to accomplish being splintered into four separate associations in four different corners of the state. So we sat down, and I remember being at the table, and I couldn’t even talk. My mouth was so dry. Then Nick called me and said, “Let’s bring this to DEFCON 5. Let’s get this done.” Because it wasn’t going to happen. We were hitting too many stumbling blocks. He, I, Lee and Glenn Villacari wouldn’t let it die. I remember Lee saying, “All you’re going to have is your trade show and your walkie-talkies.” He was being a little insulting. I said, “What does your association do for money? Golf outings?” We went at it, me and Lee. Of course, we eventually became so close I did his eulogy when he died. But that was huge. It was probably the biggest thing that happened in the industry, in not only New Jersey, but across the country. Because right now, if we’re not the top state auto body association in the country, we are absolutely top two or three. No doubt. That was the foundation of that.

NJA: You were always involved in the NORTHEAST® Automotive Services Show committee. But then when we moved it back to New Jersey in 2009, you took on a more prominent role.

ED: It was so exciting. We loved it. Watching it grow was fantastic. We had great ideas. We seemed like we had the perfect brain trust to make that grow.

NJA: Did you ever foresee it becoming as big as it has?

ED: No. I mean now it’s second only to SEMA in the country. You know why it worked out? Because when we took it back to Jersey; we had enough balls to say, “Let’s wing it. Let’s give it a shot.” And that took a lot of f#$king nerve. That took balls to move into that big space. Then we met the people at the Meadowlands. They were great. We knew right away that it was going to be strong. But it was scary. Especially when we got sued by the trade show manager we fired.

NJA: But you were the only one on the committee who wasn’t sued. Why was that?

ED: Well… (Laughs) The rumor was he was going to also sue me. So I called him and told him I felt left out. He said, “What do you mean?” I said, “I feel left out. Do you really want to alienate me like this? I want you to sue me.” And he kept asking, “What do you mean?” I said, “I’m waiting for the lawsuit. I’m going to wait for the certified mail. I wish you would sue me. I really do.” Again, he asked “Why???” I said, “I don’t know. That remains to be seen what the outcome of the lawsuit is going to look like, my friend.” (Laughter) I never got sued. (Laughs) Now, that could be perceived as threatening. But it wasn’t. I’m an insecure guy, and I don’t want to be left out. That’s all. (Laughter) He sued the rest of the committee, but he didn’t sue me.

NJA: You’ve spent almost 50 years in the industry. You are a key figure in AASP/NJ’s history. We have seen you walk into the NORTHEAST show and meetings and it’s like you are the “Godfather” of the Jersey collision repair industry. What are your thoughts on the association after 40 years working in it?

ED: I have so many great memories of this association and this industry. I met some of my closest friends in the world. Brothers. You know? And I still talk to 50, 60 percent of them. People I can walk up to at the NORTHEAST show and give a big sincere hug. It’s like being in combat. There’s a little bond when you go through a lot of the same shit. You know what I’m saying? When you’re crawling, it’s like being in a foxhole with somebody. It’s like a war reference, I guess you can say. You’re in the trenches with the same problems. So when I look back, I think of all the great people I’ve shared that foxhole with.

NJA: What are the biggest changes you’ve seen in the industry in the last 40 years?

ED: DRP and certification were the biggest changes. The push for DRP and the push for high-end certification, which is a very small market that I was in. There’s only seven or eight shops that do what I did. And it took a lot of balls and a lot of money. And I did it. I started it at 59 years old. It was a younger man’s game because there’s a lot of shit you’ve got to go through. With the right administrative staff in the office, you can do it. But it’s tough. There’s a lot of politics. You have to create a solid relationship and a strong level of trust between you and the dealership. And some guys are just like, nope, nope, just like straight out, nope. For me, I think the certifications were the turning point in my business. No doubt.

NJA: How many certifications did you have when you sold?

ED: Volvo, Polestar, Jaguar, Land Rover, Tesla, Maserati, Porsche, Mercedes-Benz, just finishing BMW. So eight. C8 Corvette because it’s a restricted car also. So nine. Nine high-labor-rate certifications.

NJA: What would your advice be to a shop that would want to do something like that?

ED: Hold on to your hat. Batten down the hatches because it gets really, really, really hard. And programs like Land Rover and Porsche are the toughest. It’s a lot of work. Anybody that does it, I give them a lot of credit.

NJA: Pre-certification, you were very much a DRP shop. Obviously, that’s always been such a controversial topic. But yet, you’re one of the few shops that was never really criticized for that. Why do you think that was?

ED: Initially I was. But I don’t know. I think it has to do with how they respected what I did and the work that I did. I always helped other shops when they asked. I was never a hog with my work or my knowledge. So I didn’t get criticized for being a DRP. Not too much. Under their breath, maybe. But, you know, everybody kind of got it 20 years later, right? Then everybody else joined. I always say, maybe I just got it earlier than the guy who complained about it.

NJA: There’s a trend here. You were on the DRP train early. You were on the certification train early…

ED: I always read the trade publications. I would sit and read every issue of New Jersey Automotive and Body Shop Business. I would go to the training at the trade show, and I’d listen. These guys were smarter than me, and I was aware enough to realize I could learn from them. That is the problem with a lot of shops. Their goddamn egos. Because they think they got it wrapped up. If they had it wrapped up, they’d be certified for eight high-paying OEM directors. But their egos keep them from listening to somebody else’s point of view. Don’t let your head get too big. It will hold you down. Try to play nice with your competition. But if your ego is in the way, that’s not going to happen.

NJA: A lot of people would say that the insurance companies are treating shops worse than ever these days. Did you see that on the way out?

ED: It started getting hard again. They left us alone during COVID. Everybody thought that was going to continue. So a lot of guys were changing their business tactics and charging over and above and all that stuff. The insurance companies…they’ve got attorneys and psychologists that sit and tell their employees how to get into the body shop’s head. They’re very smart. They adapt 1,000 times faster than we do.

NJA: I know you love being Italian almost as much as fixing cars.

ED: I had a very Shakespearean great-grandfather. So, we have a Romeo and a Juliet, a Hector and a Leo. These are all Shakespearean names. And my Uncle Romeo was the black sheep of the family. He was the wiseguy of the neighborhood of the North Ward in Newark. And he was feared and rightfully so. Because I heard the hardship my grandparents went through, yet they came here with an American flag on their lapel. My great-grandfather would say, “This is the greatest country in the world, but the greatest culture in the world was in Italy.” The one that contributed most to the world, including the Renaissance, right, the beginning, out of the Dark Ages, was Italy. So, yeah, how can you not be proud? What other country produces Bugatti, Lamborghini, Maserati, Ferrari, Versace, Armani, right? I mean, there’s no other country in the world that’s produced something so loved as Italian food, right? Listen, before we got to this country, a meal was a piece of meat with animal fat poured on top. That was a f#$king dinner, okay? (Laughs.) So, yeah, of course, I grew up very proud. I had a very old-fashioned house. My grandparents lived with us and spoke broken English, but they loved this country unconditionally. They were incredibly patriotic, and they sent their sons to war. And the most died…more Italian Americans fought and died in World War II than any other ethnic group.

NJA: When the pandemic hit, we started doing a podcast together called “Out of Body Experiences.” During those podcasts, we repeatedly brought up the fact that you’d never sell your shop. You love repairing cars too much. But then earlier this year, going back to our theme here, you got an offer you couldn’t refuse.

ED: As they say in the movie, yeah. I think this is going to be like Haley’s Comet. Listen, there’s certain companies, consolidators, that will buy anything. Certain ones like run-down, shitty, poor quality, bad-reviewed shops because all they can do is lift it up, right? All they can do is fix it, right? The company that acquired us wants to be the cream of the crop. My building’s not beautiful, never was, but they wanted my brand. That’s why they called me. I had two people pitching me at the same time. But I liked the way they talked. We broke bread, and we sat down. They were good guys. Really, they’re compassionate. My employees didn’t want that much change that quick, but I said to them, when I leave, this is going to get better. Again, ego out of the way. “No one can do it like Eddie did.” Bullshit. They’re more efficient than me. Their job cost program was stronger. Their accounting was easier. Their process was near perfect.

So really, it was about timing. I’m 66 and a half years old. A dear friend in the industry said to me, “My father died on the job, Eddie Day. Our industry is going through something right now. You’ve got to jump on it. Don’t die on the job.” I’m very blessed it worked out.

NJA: What will you miss most?

ED: The thing that I will miss most is my customers. Being able to satisfy the toughest customer. Keeping that Google rating at 4.9. Satisfying that tough customer who comes in screaming. And my people, of course, my people. We sat down for breakfast and lunch every day. We ate together every day. Nobody ate over the desk. It was a family. But it was time.

NJA: What do you see as the future of the collision repair industry?

ED: The spirit of that small shop is never going to end. That guy is going to make it work. I never counted that five-core shop out, ever. Because I think they’re the f#$king backbone. Let’s go back to World War II, right? They’re the boots on the ground. If they watch their money, that five-core shop is always going to make a decent living. There’s always going to be a little overflow for that guy. As for the technology, sub it out to the dealer, let the dealer fix the broken wire and put the light out, bring it back, add your 25 percent, get your tow bill. So technology is not a problem because you become a problem solver. And the problem solving is what? Find somebody that can fix it. That’s how you problem solve. Find somebody smarter than you. I’m a firm believer of being around smarter people than me, which lately, is easy to find. (Laughs)

Want more? Check out the September 2024 issue of New Jersey Automotive!